Sunmaker training institute boosting skill levels and bringing employers, jobseekers together

As Uganda prepares to begin oil production in the Albertine Graben region, where crude oil reserves are estimated at 6.5 billion barrels, a startup founded by four Chinese students is helping the country address its skilled labor shortage.

Lyu Jian, a master’s students from China University of Petroleum, first came to Uganda in late 2016 with classmates Gong Zhiwu, Ma Bo and Duan Xiaofei to research the African market. They soon spotted opportunities in the oil and gas sector and founded Sunmaker Energy, an industry training institute, in Kampala, the Ugandan capital.

With French company Total, along with Tullow Uganda Operations and China National Offshore Oil Corp, planning to start drilling together next year, demand for oil workers is expected to peak in late 2019 and early 2020, when an estimated 13,000 workers will be needed.

The Sunmaker Oil and Gas Training Institute expects to train more than 70 percent of the petroleum engineering technicians in Uganda.

The African nation has been actively developing its energy sector and infrastructure construction in recent years, as have other countries on the continent. Only 0.5 percent of Africa’s population are skilled workers, much lower than the 3 percent in China in the 1990s, when the situation in the country was similar to that of Africa today.

“What we’re doing is trying to train more professional and certified workers,” says Lyu, Sunmaker’s CEO.

For years, vocational training schools in China have been encouraged by the Chinese government to open branches in Africa. However, they have faced safety concerns, a lack of operation fees and employees, and inefficient communication with local governments.

“It’s easy to open a school and invest a lot in facilities in Africa, but nobody knows how to earn the money back. We’re the first Chinese in Africa to earn rewards from investment in vocational training,” Lyu says.

International enterprises that invest in Uganda are required to ensure that locals make up 70 percent of their workforce. However, many international employers have found that such workers are not necessarily competent, and training them can be time-consuming. Systematic training before employees begin working is considered by bosses to be ideal.

“It’s ridiculous that some companies hire many locals as safeguards just to increase the localization rate,” Lyu says. “We’re here to help the local workers actually work efficiently using professional skills and techniques.”

Sunmaker expects Chinese companies in Uganda in sectors such as oil, electricity, construction and agriculture will turn to the institute to train their workers.

Lyu says the company’s clients also include aid organizations based in Germany and Belgium, the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Development Cooperation Agency of China, and many other NGOs providing multilateral or bilateral aid to Africa. These organizations pay for local trainees to study at the institute.

“Multilateral or bilateral agencies choose us not only because our price is more competitive than vocational institutes opened by Westerners but also because they value China’s development experience over the past three decades,” he says.

The school, which opened a few months ago, stands 1.2 hectares of land in Kampala and has a 4-hectare oilfield, all of which was provided by the Ugandan government. Its classrooms have augmented reality and virtual reality facilities and have so far been used to train 1,000 skilled workers.

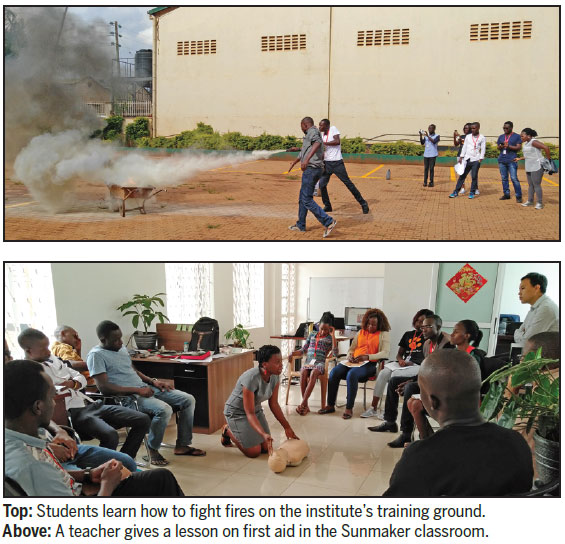

The curriculum is separated into two parts – theory and operation. Teachers are experienced and certified welders, plumbers or bench technicians from China, Egypt and South Africa. Senior technicians, engineers and managers from international companies are also invited to give lectures.

Sunmaker’s co-founders are creative in many ways. To guarantee sufficient teachers, the best graduates from Sunmaker with internationally recognized certificates are allowed to stay and teach. The institute also holds regular talent exchange activities by bringing human resource managers from Chinese companies together with African jobseekers. This allows the institute to learn more about the employers, and jobseekers can learn more about the institute.

“We’ve chosen a path that no Chinese has traveled in Africa,” Lyu says.

Sunmaker plans to open a school in Lagos, Nigeria, next year, as well as four more across Africa. Lyu says his goal is to establish 15 training bases in 15 countries in five years.

In addition to companies and international NGOs, the institute’s doors are also open to any individuals who want to polish their vocational skills and improve their job prospects.

For example, Lyu says, a welder paid 1,500 yuan a month ($215; 190 euros; £167) could turn to Sunmaker to upgrade his or her skills. The tuition fee for two months of intensive training is 6,000 yuan, but it can be paid after they get a new job.

After completing the training, the welder receives an internationally recognized certificate and could earn 3,000 yuan a month. The school will then charge him or her 1,000 yuan a month until the tuition is paid off. This, says Lyu, is why Sunmaker attracts so many people who want to improve their lives.

“Hopefully, we can attract many students through our policy of ‘training first, tuition second’. Our goal is to train 10,000 skilled workers in each center each year, and 150,000 workers will be trained across Africa.

“In this way, we’re actually changing the structure of Africa’s human resources. We’re changing Africa.”

Compared with most Chinese vocational training institutes, Sunmaker is privileged in two aspects, according to Lyu. “We’re good at communicating with the local government. We can get policy support from the government because they’re convinced we can lift the quality of people’s vocational skills. The other advantage is we can survive in the market and make a profit.

“We always talk about building a community of shared future for China and Africa,” Lyu adds. “It is not about how many roads you build in Africa, but about how much we understand that people in China and Africa have the same desire for a better life.”

As part of the capacity building initiative launched at the Beijing summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in September, China will set up 10 Luban workshops in Africa to provide vocational training.

Luban workshops are named after the father of Chinese architecture, who lived around the fourth century BC. The program is designed to offer technical and vocational training, promote modern vocational education reforms and enhance collaboration among vocational schools worldwide.

Lyu considers this as a good opportunity for Sunmaker to have deeper cooperation with Chinese vocational schools determined to go overseas.

Ningbo Polytechnic is among the Chinese institutes that have been inspired by Lyu and his colleagues in Africa.

Cen Yong, a member of the Party committee at Ningbo Polytechnic, says: “I really admire the four young entrepreneurs in Africa. They’ re insightful, passionate and ambitious. … We appreciate Sunmaker’s idea and the concept of their operations in Africa, and hopefully we will have good cooperation in the near future.”